Jumping to Conclusions

Forty years after its creation, the jump cue is still a controversial topic, although its impact on the game can’t be disputed.

By Keith Paradise

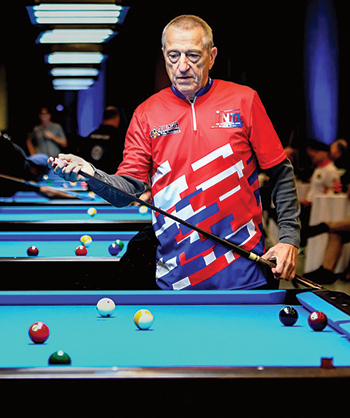

Playing in the semifinals of March’s Predator World 10-Ball Championship in Las Vegas, former world champion Fedor Gorst found himself in a difficult situation.

With the 9 ball blocking his path to the 5 ball near the corner pocket, he grabbed his jump cue and swiftly popped the object ball into the corner pocket. After landing the ball, the cue ball rolled behind the 8 and the Russian, with the jump cue still in hand, quickly jumped over the obstruction and rolled the 6 ball into the side pocket with a slight cut shot. Again, the cue ball refused to cooperate, now drifting behind a 10 ball that now blocked his path to the 7. Gorst once again used the black carbon fiber cue to pocket the 7 on a bank shot but this time scratched in the far corner pocket, as the crowd at the Rio All-Suites Hotel and Casino groaned at the misfortune before ultimately cheering the performance they had just witnessed.

Sanchez Ruiz held on for the win, but Gorst walked away with one of the most talked about moments in the tournament.

Forty-years ago—even 20 years ago—if you wanted to watch professional pool players sending cue balls airborne to pocket balls like this there was a better than good chance you were probably tuning into “Trick Shot Magic” on ESPN, a series of televised trick shot competitions promoted and aired on the network. But as cue manufacturers have continued to introduce jump cues into the professional game, players have developed a proficiency with the tool to the point that being able to jump accurately has become as critical a skill to learn as breaking and position play.

Over four decades after its almost accidental creation, the jump cue has slowly grown to become the third cue that virtually every professional player carries in their case.

“I think the top players are starting to get it,” said Gorst in a phone interview from the Philippines. “Five years ago, it was more about who was breaking better. But now, since they’re changing the break and rack formats, it leads to a lot of safety battles where you have to jump.”

“The jump is becoming more and more a really big part of the game,” said Billiard Congress of America Hall of Famer Ralf Souquet. “Because of the new equipment over the last five to 10 years, if you’re a certain height and if your fingers are long enough, you can jump quite easy. I’m not saying you’re going to make the ball but you’re going to clear the object.”

As is usually the case with new technology in any game—such as the hybrid club in golf—acceptance and proficiency at the pro level has now trickled down to the amateur ranks as well. Not surprisingly, the increase in demand had led to more manufacturers making and selling the sticks. According to Kyle Nolan, product development lead at Cuetec, the brand’s jump cue sales have grown by more than 50 percent year after year for the past four years. Online retailer Pooldawg currently has 24 jump cues for sale from approximately 10 different manufacturers, with many of the higher priced carbon fiber models made by Predator and Cuetec currently out of stock.

“I was pretty surprised by it too, but we have a really hard time keeping the carbon fiber jump cues in stock,” said Keven Engelke, General Manager for the popular online retailer. “When we have them, they definitely are moving.”

Even some professional players are getting into the action, with brothers and former world champions Ping Chung and Pin Yi Ko developing their own line of jump cues which were introduced onto the market in the last couple of years.

Jump cue technology has come a long way since the “short sticks“ used by Nick Varner in the early ’90s.

“Because we practice our jumping every day, we can jump a little bit better than the average player,” said Ping Chung, former World 10-Ball Champion, in a text message. “It was because of this reason that we wanted to do our own jump cue.”

While the cue started as a tinkerer’s invention and evolved into a staple in the artistic pool industry before ultimately becoming entrenched in the pocket billiards game of the 21st century, the jump cue is not without controversy. Of all the modern inventions that have been created over the last half century designed to make the game easier—carbon fiber shafts, low-deflection shafts, break cues and composite tips—the jump cue might be the one that has created the most debate, with some promoters and leagues still prohibiting them four decades after their invention.

Regardless of the variance of opinions, the game is more three-dimensional than it has been in the last 100 years, and with the recent improvements that have come on line in recent years, shots like what Gorst pulled off in Las Vegas might only be the beginning of what’s to come.

Pat Fleming was messing around with a masse cue on his home table around 1981, attempting to curve the cue ball around a blocking ball towards his target.

While attempting to shoot around the nuisance sphere, he watched as the cue ball jumped over the ball instead. He stood there for a moment puzzled. Why did it go over when he wanted it to go around? More importantly, he wondered if he could make it happen again. And so, he tried it and it did. And then again. And again.

“All of the sudden, I realized that I could jump balls with this cue,” said Fleming.

He took it to Long Island cuemaker Pete Tascarella, who was just starting his cue-making operation after acquiring the late George Balabushka’s equipment, and asked him to build an extension for this cue out of lightweight balsa wood. Fleming then headed to Florida where he used his invention in a tournament.

“I was jumping balls like crazy and, of course, no one had seen this before,” said Fleming. “Then I started using it everywhere that I went.”

Conversely, Tascarella saw what Fleming was able to do with the shortened cue and developed a breaking cue that would disengage about halfway between the joint and the butt end, one of the earliest models of a jump-break cue. He made and sold a handful and a friend suggested he patent the design, but he sold such a limited volume of cues he didn’t think it was worth the energy.

Meanwhile a time zone away, Sammy Jones had perfected getting a ball airborne simply with the shaft of his two-piece cue, becoming proficient at gambling games which involved him playing with or executing jump shots with the top half of his cue. Gambling and hustling in the South in the early 1970s, Jones had mastered the art of coming up with gimmick games to win money. He eventually perfected a trick shot over time where he could jump an entire rack of balls with the shaft.

Fleming was simply testing a masse cue when he realized how easy it made jumping balls.

“It was kind of a neat feeling to be able to do that,” said Jones. “Not everyone could do it because no one really knew what it was all about.”

When Fleming learned of this skill, he assumed that Jones had developed some sort of trick shaft that could vault a ball over a blocker. When he was in Kentucky a few months later for a tournament and ran into Jones, he asked him about this rumor that he had heard. After Jones confirmed the rumor, Fleming waited for him to pull out some contraption from hie case. Instead, Jones asked to borrow Fleming’s shaft and casually jumped the cue ball over an object ball.

By now, he had picked up the nickname “Jumpin’ Sammy Jones,” eventually having a handle made for the shaft that he would use in competition. He slowly noticed that the crowd clapped for certain things during a match, such as a pocketed 9 ball on the break and when he made a jump shot with his new contraption.

“So, this was pretty cool,” said Jones. “And then everyone started getting a jump cue.”

Well, not everyone.

At this time, only Jones, Fleming and fellow player Dave Bollman, an employee at Q-Masters in Norfolk, Va., who also built cues, were the only competitors carrying a dedicated cue for jumping. As is usually the case when someone comes out with something unconventional, there was some backlash, most notably from Earl Strickland, who had developed his own technique for jumping balls with his playing cue. In fact, one of the most memorable shots of Strickland’s young career occurred when he executed a jump shot against Steve Mizerak in the final of the 1983 Caesars Tahoe Classic which was broadcast on ESPN.

Fleming recalled arriving at one of the U.S. Open 9-Ball Championship tournaments at Q-Masters and being approached by Jimmy Reid and a handful of fellow players. They had decided that Fleming could use his cue, as long as everyone else could as well. By the late 1980s and into the early 1990s, a handful of jump cues were hitting the market, although many of them were cues in name alone. Some were simply a wooden dowel with a hardened tip on the end, some were short aluminum rods and a couple resembled miniature baseball bats. Since there were no specifications outlined by the Billiard Congress of America or the fledgling World Pool-Billiards Association, there was not a true limit on what could and couldn’t be qualified as a jump cue. After visiting the 1994 BCA Trade Expo, Billiard Digest writer Mike Shamos reported the following:

“Among the most popular products at the BCA Trade Expo were jump cues. They came in all shapes and sizes, from a short six-ounce model that felt like balsa wood to an imposing black aluminum monster with 19-millimeter tip that resembled a cattle prod.”

Before jump cues were common, “Jumpin’s Sammy” Jones gambled using just the shaft.

In the same article, Shamos reported that the Professional Billiards Tour, then the preeminent men’s series, had recently outlawed the cue, while the Women’s Professional Billiards Association had never allowed them in the first place.

“In my opinion, that was very short-sighted,” said Jones. “First and foremost, it’s a great shot and especially to be able to sell another product in the industry. I’ve always been an entrepreneur at heart. It just didn’t make any sense that great players didn’t want to learn that shot.”

And the sticks were popular, especially with the public at trade shows. While developing his trick shot demonstration in the mid-1980s, Tom “Dr. Cue” Rossman would use one of the early jumpers developed by Gene Albright called the Kangaroo Cue, which was about 16 inches long and about 20 millimeters at the tip—a tip he told the crowd was “nitrogen gas-injected” to jump balls. He collaborated with a Minnesota inventor named Brad Boltz on his own line of cues, naming the product the Happy Hopper and inscribing a small rabbit on the butt end of it. He started ending his shows with a trick shot where he lined up a row of balls and jumped them over another line of balls into the side pocket, then told the crowd that they too could have a Happy Hopper for $225.

“Tom’s wife pulls out like a gym bag underneath and they sell like 30 of them in five minutes,” said John Barton, founder of JB Cases, who caught Rossman’s act at a BCA event. “And I mean, people can’t pull their money out fast enough.”

“It was an amazing income that we had off of these cues and, all of the sudden, everyone in the industry was coming to the booth and we sold out of them,” said Rossman.

Barton had his own jump cues for sale at his booth and began playing around with it after seeing Rossman’s act. He developed a new flared-handle cue with German cue makers Hans Joerg Bertram and Oliver Stops and a jump routine of his own. Soon, Barton’s Bunjee line was available for sale at the same shows, with Barton executing a similar series of shots during a demonstration.

The jump cue that might be the most notable of the era was The Frog, a product that was designed by a southern California mechanic and inventor and given to Robin Dodson to try out while she was practicing one afternoon at her home pool room. A two-time World 9-Ball Champion, Dodson didn’t even know how to jump a ball until she was taught how to properly use the stick.

“As soon as I jumped a ball I was like, ‘Oh my goodness, this is a game-changer,” she remembered.

Today’s players, like Shane Van Boening, jump with pocketing and position accuracy.

When she was able to secure a manufacturer who could mass produce the cue, she was given the rights to the product and began selling it at her booth and advertising it in publications. A naturally charismatic saleswoman, Dodson was soon earning more at her pro shop booth at tournaments than she was in the competition, sometimes taking home $30,000 in a weekend. Over time, she found herself wanting her matches to be completed sooner so she could get back to the booth.

“We would bring 500 jump cues and come home with maybe 100,” said Dodson. “I mean, it’s crazy but I just sold it.”

In 1994, members of the Billiard Congress of America’s board of directors met in Arlington Heights, Ill., site of that year’s World 9-Ball Championship and debated rules and specifications for the cue and chose Dodson’s Frog as the template for standard length: It must be at least 40 inches. A standard that stands to this day in the rulebooks.

“It had the most prominence as a jump cue at that time because Robin did a little more advertising and it was probably the best-known jump cue,” said John Lewis, a BCA employee at the time. “We didn’t want to disallow it and so from then on, 40 inches is what they went by.”

Although cuemakers and inventors were coming to market with jump products, not all of them could do the job, whether it was due to having too narrow of a shaft diameter, weight distribution or tip softness. Some were simply shafts with short handles. When Dodson gave demonstrations at her booth to try and teach customers how to jump, she would have the customers dig out their own jump cue to try first to see if it worked. If theirs worked as well or better than hers, she told them. What she found was that some of them couldn’t lift a cue ball at all.

“The function of the cue has a lot to do with tip hardness and leather tips just frankly aren’t hard enough,” said Brandon Jacoby, who has been involved with his father’s Jacoby Custom Cue company for 30 years. “There were a lot of cues on the market that didn’t function really well because they just didn’t have a hard enough tip.”

When the extremely hard phenolic tip was created and installed about 25 years ago, suddenly almost anything had a jumping capability.

“Everything about that tip changed the jump shot, in my opinion,” said Dodson, who eventually transitioned to teaching the jump shot before retiring from competition in 2002. “The fall of the Frog was the phenolic tip because once everyone had that, then their jump cues were nicer.”

“You could put a phenolic tip on a broom, and you could jump with it,” said custom cuemaker Ned Morris, who chose instead to experiment with a hardened leather tip since the chemical compound had the ability to potentially damage balls.

After creating the type of tip he preferred, Morris developed the first three-piece jump cue—a device that Mike Massey used to win a handful of artistic pool championships—then partnered with Stealth to create the Air Time 1 cue around 2000, with Morris estimating that the item sold around 15,000 units overall.

Dodson pocketed more selling her “Frog” than from winning titles.

Early in the 21st century, with the Pro Billiards Tour no longer in operation and the WPBA loosening their prohibition, production cuemakers took a bigger interest in the product, realizing it was yet another piece of equipment that could be marketed to consumers. Japanese manufacturer Miki, the company that produces the Mezz and Ignite lines, introduced its first dedicated jump cues the same year and Jacoby collaborating with local cuemaker James Peterson to build the first edition of the Jacoby Jumper in the early 2000s. Around the same time, Predator introduced the original Air series. “When we entered the market, the jump cues that were on the market could jump but they weren’t really accurate because they were heavy with phenolic on the front end,” said Philippe Singer, Vice President of Predator Group. “We put a lot of research into making a jump cue jump better and be accurate. What we found was that it couldn’t be too heavy because if its too heavy you don’t get accuracy on your jumps.” Whereas the early jump cues focused on weight more towards the front of the cue, Predator began engineering sticks that were lighter on the front end, and also experimented with cues made from different materials. According to Singer, the real game changer in terms of accuracy was the development of carbon fiber, which was introduced on the Predator’s Air Rush jump cue about five years ago. According to Singer, the material naturally has more spring than wood and the tube itself is lighter, which helps with weight distribution. “Now it’s a lot easier to pop the cue ball,” said Singer. “Carbon fiber is just a superior material for restitute force, which is the first thing that helps.”

With big name manufacturers like Cuetec and Predator now involved in the creative process, the days of inventors and garage engineers has given way to collaborative efforts between the companies and the competitors they sponsor. When Gorst first picked up a cue stick almost 15 years ago, he could barely get a cue ball into the air. While practicing on a cramped table in the family home in Moscow, he occasionally needed to switch to his Jacoby jump cue out of necessity due to a wall being in the way and slowly increased his proficiency with the shot. Now sponsored by Cuetec and established as one of the best jumpers in the game, Gorst has worked with the manufacturer on the current line of jump cues and offers feedback, as does Florian “Venom” Kohler,” the professional trick shot artist and social media sensation who is also sponsored by the manufacturer. Nolan said that the company seeks feedback from the professional players they sponsor and value their input but that their contributions need to go beyond just having talent. “If they can’t articulate the differences and can only tell you one cue is better than another, you won’t make much progress,” he said. “The key is to maintain your focus and develop a product that elevates the execution for amateur and professional players.”

How would a star like Woodward’s game change if promoters and tours still outlawed the jump cue?

This was the objective when the company was working on the current line of Propel jump cues. Cuetec tested the product with professionals and an amateur player focus group and were experimenting with both a 13- and 13.9-millimeter shaft. The pros had little issue with the thinner shaft, but the amateurs kept adding unwanted spin because of the narrower diameter and subsequent smaller sweet spot. As a result, Cuetec proceeded with a 13.9-millimeter model, which Kohler used to set a Guinness world record for longest jump shot (9’1” over two tables).

Singer said the next evolution could be the creation of a line of jump cues that is built specifically with the advanced and recreational player in mind, since both are looking to accomplish different objectives with the shot. A professional player is not only looking to pocket a ball but also control the cue ball for position after the shot, whereas a once-a-week league player who doesn’t practice jump all that frequently is looking for a stick that will simply get the cue ball airborne easier.

“The needs of a pro are not always the same as a league player or the average buyer of the product,” said Singer. “There’s room to answer different needs with different products and segment the market.”

As carbon fiber and engineering have increased the accuracy of these cues over the last decade, the most recent improvement is again with tip technology. Composite tips made of resin and fiberglass, like Tiger’s Icebreaker and the G10, are giving players an additional element of control over their jumps, allowing them to use English and play for position after the shot without sacrificing hardness.

“Jump cues used to be focused on just being easy to jump performance and if it can be used for short jumps,” said Kaz Miki of Miki through email. “People thought that was a good jump cue 20 years ago, but now we are looking for not only easy to jump performance but cuemakers are trying to develop jump cue performance with spin control. Cue ball control is more and more important these days.”

Coincidentally, many of those custom cuemakers who helped create the niche no longer dabble in constructing jump cues. Tascarella is still crafting cues in the same style as the man whose equipment he purchased, but he contends that the man hours and materials involved in making a jump or jump-break cue simply isn’t worth the man hours that could be spent building a playing cue. Morris echoed the sentiment, devoting his time to producing playing cues for his customers.

“I’m just really proud of what I did,” said Morris. “I never knew it would go this far.”

Prideful too are some of pioneers who executed the shot at the table.

“It’s rewarding to watch something that you know you had a part of,” said Jones. “It’s rewarding to see these guys who have really taken it to a higher level. They learn how to aim it from all distances and that’s admirable, in my opinion.”

Although the cues have grown in popularity, it still isn’t an instrument that is universally accepted by league operators and tournament organizers today. The Derby City Classic, Mike Zuglan’s Joss Tour and the American Poolplayers Association prohibit the use of these sticks. Competitors like Dodson and performers like Rossman, who have not only worked with these cues but also marketed them, advocate for their permission with the caveat that the stick doesn’t make the shot; that it still comes down to technique.

“I don’t care how much technology you’ve put in a jump cue I don’t think that’s helped me make the shots,” said Rossman. “I think what has helped me make the shots is the time I’ve spent on the table practicing and learning how to use it.”

No Worlds Left to Conquer

At 38, American Shane Van Boening finally claimed the one title missing from his trophy case — the World Pool Championship.

By Keith Paradise

Photos by Taka Wu

The night before the final day of competition in the World Pool Championship, Shane Van Boening slept like a baby — and maybe that should have been his indication.

“I felt like I slept the best that I ever could before the finals,” said “I just had a feeling that I was going to do well that day.”

Near the end of previous World 9-Ball Championships, Van Boening tossed and turned his way to something that resembled a couple of hours of sleep on paper but wasn’t particularly restful. This time, the 38-year-old American star guesstimated that he grabbed 10 hours of rest before rising for the final two rounds of play Sunday morning at Stadium MK in Milton Keynes, England.

Then again, nothing about this tournament had been going the way it had gone in previous years, so why should rest be any different? Throughout the five-day, 128-competitor event, Van Boening seemed to get just the right break at just the right time — or, as was the case in his round of 16 match against Ko Pin Yi, back-to-back breaks at just the right time. Whenever it seemed a player was about to take command against the South Dakotan, an untimely error would occur. Conversely, whenever Van Boening had a chance to seize on an open opportunity he rose to the occasion and shot more precisely than a Swiss timepiece.

Van Boening said he felt like a new person when he woke up and, by the end of the day, he was definitely a different one; a person who could finally add the title “world champion” as a prefix to his name, having survived a nip-and-tuck battle in the first half of his match with defending champion Albin Ouschan only to have another one of those momentum swinging shots lead to winning eight straight racks and coasting to a 13-6 victory. The World Pool Championship title, a title which had eluded the South Dakotan for a decade and a half, puts an exclamation point on a career that includes five U.S. Open 9-Ball Championships, four Derby City Classic 9-Ball titles, a pair of World Pool Masters crowns and more than a dozen U.S. Open 8-Ball and 10-Ball titles. Even before this championship, the only thing that was keeping him out of the Billiard Congress of America Hall of Fame is the fact that he’s too young, still three years from earning a spot on the ballot.

“I only have one thing left to say,” Van Boening said on the Tuesday after his victory. “That monkey is no longer on my shoulder.”

It was a monkey that had been there for so long and had been fed so often by Van Boening’s detractors that the primate could probably run a couple of balls himself. Sure, they’d say, “He’s won a lot in America but what about his record in world championships?”, completely overlooking the fact that Van Boening was one of the few American competitors at that time willing to challenge himself in international events. In consecutive years, Van Boening lost in the final, losing to Pin Yi Ko in 2015 and to Albin Ouschan the following year. In 2018, he finished third. Even in last year’s World Pool Championship, Van Boening appeared to be cruising along in the single-elimination phase when sparring partner Oliver Szolnoki came from behind to eliminate him in the round of 16. With younger players joining the circuit every year, it was understandable for American pool fans — and even Van Boening himself — to wonder if the window of opportunity was either beginning to close or had already been shut.

Van Boening opened double-elimination play with routine victories against Waleed Majid, 9-4, and Jan Van Lierop, 9-6, but struggled against Bahran Lofty in the opening round of single-elimination play, using a couple of pocketed 9 balls on the break gut out an 11-9, win. And when a resurgent Mika Immonen built a commanding 10-3 advantage in the race-to-11 round of 32, it looked like Van Boening’s chances for a championship would have to wait for another year.

“I thought it was over,” he said. “I was pretty much done.” As Immonen worked to clear the table in what could have been the final game, the 3 and 4 balls remained clustered in a corner. The former World 9-Ball Champion cut in the 3 ball and crisscrossed the cue ball across the table to try and land an angled position on the 4 ball. Instead, he bumped the object ball and left himself a straight-in shot down the rail, eliminating any hope of moving the cue ball to the other side of the table for position on the 5 ball, which Immonen ultimately overcut and missed.

“That’s when I told myself I’m not giving up,” said Van Boening. After a victorious safety exchange allowed him to cut the deficit to 10-4, the South Dakotan used back-to-back breaks and runs to chop the lead to 10-6. He would miss the 3 ball in the 17th rack but watched the cue ball roll to a safe spot, forcing his opponent to try a jump shot. After Immonen missed his attempt, Van Boening cleared the table once again to trim the lead to 10-7.

It seems no championship run in any sport is complete without some form of controversy or point of contention. Pool, with its myriad of breaking and racking rules, is rarely an exception to the rule. After Van Boening broke the balls in the 18th game, the official approached the table to remove the template rack that was being used in the tournament’s earlier rounds. The 9 ball settled near the plastic sheet, with the 1 ball slightly behind and to the side of it. Van Boening said the object ball was slightly hidden by the 9 but that he could see one-quarter of the ball. Rather than use a ball marker to mark the area where the 9 ball was, the referee opted to simply pick the ball up and place it back down again, much to the disdain of Immonen, who grumbled noticeably after Van Boening cleared the table to narrow the gap to 10-8. Van Boening, who was unintentionally blocking Immonen’s view of the table after the break, stated the 9 ball was placed back in its proper spot.

“You can’t really say that if you didn’t really see the 1 in the first place,” said Van Boening.

Immonen, meanwhile, said his main complaint was about officials touching and moving balls without the aid of a ball marker. Immonen took time prior to the next break to voice his displeasure with the referee. Viewers on social media immediately chastised Immonen for his protest.

“I just can’t fathom the audacity that people have,” Immonen said. “I just wanted to make a point that I don’t want him touching the balls without a marker.”

Van Boening forced an Immonen foul in the next game to trim the deficit to a single rack. Van Boening was feeling it. When he muffed position on the 7 ball by accidentally kicking the 9 ball into its path in the 20th game, he simply executed a rail-first cut shot to pocket the ball in the corner pocket to tie the match, 10-10. After breaking in the deciding rack, Van Boening executed a sharp cut shot on the 1 ball, a dicey 4 ball with the cue ball pinned to the rail, then hammered in a punch on the 5 ball that allowed him to crack a joke with the crowd when it landed. He finished off the rack to advance to the round of 16 while his opponent packed up his cues and wondered what could have been.

“I basically missed one ball and played two jump shots and two kick shots,” said Immonen. “If I get good position on the 4, I’m clear out. One positional error cost me the match. I just want that match to be remembered for the quality of play and not the questionable little details.”

Van Boening had survived to the final 16 but still wasn’t playing as well as he was capable of. Reflecting on his matches, Van Boening said he realized he’d forgotten a key ingredient: fun.

“I forgot that I need to have fun when I go and play in all of these tournaments,” he said. “To just take away the pressure on yourself and getting out there and playing the table and playing your game.”

He was given a bit more advice during the event that proved crucial. The morning after Van Boening’s comeback victory against Immonen, he had breakfast with longtime sparring partner Jeff Beckley. As they shared a long chat, Beckley reminded his old friend to stay positive and maintain composure throughout the whole match.

He would need all the positivity he could muster down the stretch as his route would include former world champion Pin Yi Ko, Jung-Lin Chang, considered among the best rotation players in the world, reigning World Pool Masters champion Alex Kazakis and defending World Pool Champion Ouschan. If a Hollywood writer had submitted this script, it would have been rejected as being over-the top as each competitor held some significance to Van Boening. Ko and Ouschan had both defeated the South Dakotan in world 9-ball finals, while Kazakis whitewashed Van Boening in the finals of the 2021 Masters, 11-0.

Opening the day against Ko, again Van Boening watched his opponent build an early lead, as the former World 9-Ball and World10-Ball champion led, 7-4, and was in the process of adding to his total with an open table. Once again, a fortuitous miss allowed the American back to the table. Van Boening completed the rack, then rifled in back-to-back 9 balls on the break to tie the match. From there, he ran through the final three games to gut out an 11-8 win.

“That’s pool,” said Van Boening. “I didn’t give up and just played the best I could, but he made more mistakes than I did, and I just took advantage of his mistakes.”

Next up was Chang, who won the International Open in 2018 and the Las Vegas Open 10-Ball tournament in 2020 but has experienced similar struggles in world championships. He reached the finals of the 2019 World 9-Ball but got bogged down by pressure and lost to Fedor Gorst. Van Boening also played the 36-year-old from Chinese Taipei in a gambling match last year in Texas and watched the effects pressure had on his opponent during the multi-day event. Van Boening’s plan was simply to get ahead early and watch the stress devour Chan, which is exactly what happened. Van Boening built leads of 5-2 and 7-3. Chang whittled away at the deficit both times and even cut the lead to 10-8 before handing the table back to Van Boening and losing, 11-8. Van Boening was heading to the semifinals the next day to face Kazakis (who had survived a hill-hill match against Szolnoki in the quarterfinals) and to bed for that good night’s sleep.

Playing in the second semifinal match of the morning, the American recovered from an early 3-2 deficit to jump out to a comfortable 8-3 lead. The Greek wasn’t finished, fighting back to cut the lead to 8-7.

With a chance to tie, Kazakis unleashed a powerful break which pocketed six balls. The problem for him was that one of those was the cue ball. Van Boening cleared the table to climb ahead 9-7, then used one more break-and-run and a combination shot to squeak out an 11-7 victory and earn his third shot at the title.

“Shane is an amazing player and very tough to beat,” said Kazakis. “I had some weird breaks that helped me to lose in that match but, overall, he played amazing against me.”

Heading into his championship match against Ouschan, Van Boening said he felt confident. He believed he was breaking better and had put together more multi-rack packages than anyone else. Add in the fact that the winner breaks format, changed from the previous year’s alternate break setup, favors a player like Van Boening and it was easy to see why he was feeling good about his chances.

That said, Ouschan didn’t win back-to-back Premier League Pool events, last year’s World Pool Championship and the International Open on good rolls alone. In fact, if anyone was playing better down the stretch in Milton Keynes, it was the Austrian. After opening with easy victories against Lo Ho Sum and Daniel Maciol, Ouschan gutted out an 11-6 win over Nicholas De Leon and an 11-8 decision against Mats Schjetne to secure his spot in the final 16.

From that point, the two-time World 9-Ball champion made it look easier and easier as he went, cruising past Thorsten Hohmann 11-5 and taking out Joshua Filler, 11-6, to advance to the semifinals where he met Abdullah Alyousef, a 20-year veteran who was following a similar pattern to countryman Omar Al Shaheen a year earlier. Last year Al Shaheen’s runner-up finish to Ouschan in 2021 was a watershed moment for players from the Middle East. This year it was Alyousef’s turn, as he upset Aloysius Yapp and Max Lechner to reach the final four.

“After Omar’s performance last year, a lot of things changed in Kuwait,” Alsousef said. “It motivated a lot of players, and the game grew up more and more.”

Unfortunately for Alyousef, Ouschan picked the semifinals to play perhaps his best match of the event, breaking and running four times in eight racks to build a commanding 8-0 advantage. The Kuwaiti cut the deficit to 8-3, but missed in the next game, allowing Ouschan to coast to an 11-3 win to secure a spot in the final.

“I put some pressure on myself because I was the person that people wanted to beat,” said Ouschan. “I played good enough to beat my opponent in most of my matches but when I got into the knockout stage I played better and better every game.”

In the title match, Ouschan took advantage of some early jitters by Van Boening to build a 4-2 lead. But theAustrian scratched on the break in the seventh rack and Van Boening cleared the table and tacked on a break-and-run to tie the match, then used a combination shot on the 9 ball to grab the lead.

Throughout the day, Van Boening had been experimenting to see which side of the table was better for breaking. Generally, he favors the right side but was struggling to put balls away from that area of the table throughout the day. In fact, two dry breaks against Kazakis allowed the Greek back into the match. So, when he broke in the 10th rack, watched as nothing fell, then sat and watched while Ouschan cleared the table to tie the score, a tactical decision was made.

“When I had a couple of dry breaks that’s when I said to myself, ‘I’m not breaking from this side anymore,” Van Boening said.

Now he just had to earn an opportunity to break again. The Austrian had laid down a safety which he was certain had locked up his opponent. Van Boening assessed the table, then unleashed a medium speed, one-rail kick which pocketed the 1 ball, then used a safety on the 2 ball to work his way out of the rack and tie the score, 6-6.

“That’s a kick you probably make one in 20 times at that speed,” said Ouschan. “After he made that I kind of said to myself, ‘God damn. What’s going to happen next?’”

Little did Ouschan know at that time that he wouldn’t really see another good opportunity. Van Boening earned seven consecutive racks to coast into the title, putting on a display of clutch shot-making and suffocating safety play down the stretch. He rolled to an 11-6 lead, while Ouschan could only look on with a bemused look on his face.

“I know the feeling when every detail goes your way,” he said. “I knew the chances of me making a comeback were very small.”

With the lead now 12-6 and a rack away from victory, Van Boening executed a push out on the 1 ball after the break. Rather than risk a miss or selling out the table to his opponent, Ouschan returned the table to Van Boening.

“I was surprised he gave that back because that was an easy kick safe,” said Van Boening.

“I had been sitting in my chair for 25 minutes,” said Ouschan. “The chances of me leaving a good safety were very small.”

After a Van Boening safety, Ouschan returned to the table and jumped in the 1 ball, only to leave himself another jump on the 2. The long jump resulted in both the 2 and the cue ball leaving the table, handing Van Boening ball-in-hand. As he worked his way through the final balls, Van Boening admitted that his emotions started to leak to the surface. A ball away from victory, Van Boening called for his attention and walked over to the championship trophy perched on a table in the corner of the playing arena. He reached toward the trophy and said to himself, “This trophy is mine.”

After pocketing the championship-winning ball (becoming the first American since Earl Strickland in 2002 to claim the title) and shaking hands with Ouschan, Van Boening climbed onto the Diamond table and let out a series of screams that had been over a decade in the making.

“I’m happy for him,” said Ouschan. “I know that he’s suffered a lot with the two finals in a row that he lost. After the match I saw his relief and I know how he felt. He did a great job and he’s a well-deserved winner.”

The day after his championship, Van Boening upgraded his flight home to first class, had a more than modest number of adult beverages at the airport bar and headed home — again, sleeping like a baby. Of course, it’s a little bit easier to sleep when there’s no longer a monkey on your back.

“That monkey has gone back into the forest,” Van Boening said with a laugh.