For the Record

John Schmidt’s majestic 626-ball run was the culmination of years of single-minded effort and required a dedicated support team and incredible mental fortitude.

Story By Mike Panozzo

For John Schmidt, it was always personal.

At least, it became personal that day 25 years ago when fellow pro Bobby Hunter introduced him to straight pool.

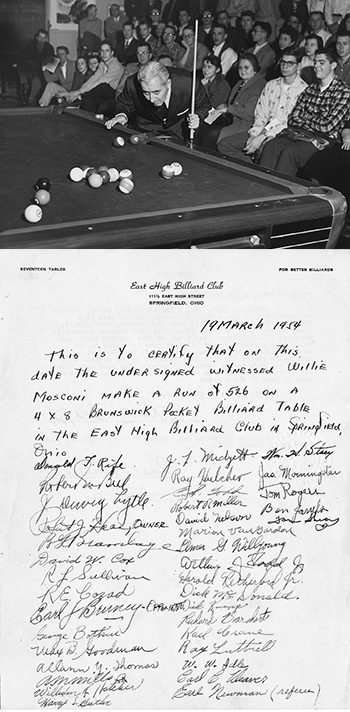

“We were in a poolroom and he was showing me how to play straight pool,” recalled Schmidt. “The first thing I asked was, “What’s the all-time high run?” I’ll never forget it. About nine people in the room all chimed in at the same time, “Willie Mosconi, 526 balls, Springfield, Ohio, 1954.” I knew right then that this was THE record in pool. This was the number EVERYBODY knew.

“Then I looked at all the photos of Mosconi. He was always dressed so dapper. You could tell he was a man respected and revered. I started wondering, “Am I good enough to even get close to a number like that?””

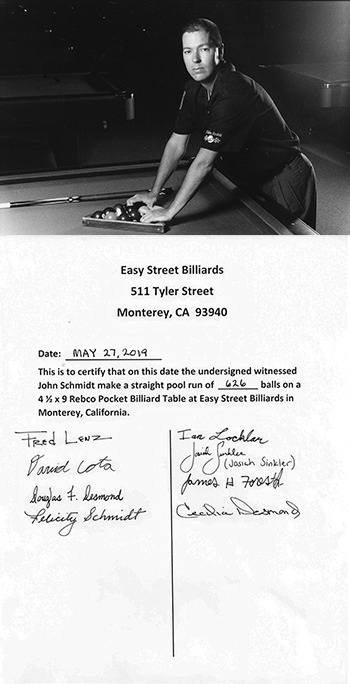

The answer, of course, was yes. On Memorial Day 2019 in Monterey, Calif., Schmidt not only got close, he actually realized the feeling of staring down that very number.

“Once I topped 500,” Schmidt recalled, “and got to the break ball at 504, the panic, nerves, fear, etc., all set in. I don’t know how I didn’t dog it.”

And when ball number 527, the 11 ball, was all that stood between himself and pool immortality, Schmidt found himself overwhelmed by the moment. He paused, put down his cue and excused himself to the men’s room at Easy Street Billiards, the room he all but lived in for 54 days during three extended visits over a 14-month period.

“A bit of a crowd had built up and I was starting to get a little teary-eyed,” Schmidt admitted. “I wasn’t worried about gushing into tears, but I was watering up a bit. I needed to just be by myself for a minute. I splashed some water on my face and gathered myself.”

After taking a deep breath, Schmidt marched back to the table, looking anything but Mosconi-esque in a golf shirt, blue shorts (“I wore them every day because they’re so comfortable!”) and Hoka shoes. With his wife Felicity, benefactor and rack caddy Doug Desmond, and California cuemaker Jerry McWorter sitting silently off to the side, Schmidt lined up the shot he had fantasized about over the years. The 11 ball was just six inches from the corner pocket and the cue ball was eight inches behind. The shot was at a slight angle.

“When I first hit it, my heart stopped,” said Schmidt. “I had the whole pocket but I knew I hit it thick. It went in, but it was into the left side of the pocket. I didn’t want to touch a face as it went in.

“I thought to myself, “My god, if I’d missed a hanger at 527 I would have stepped into traffic.””

With the weight of 20-plus years obsessing over Mosconi’s storied mark lifted, Schmidt settled back into a natural groove. He rattled through six more racks before missing on a combination shot. His record-shattering run had reached 626 balls.

“This number meant so much to me,” Schmidt understated. “I feel like I have been chasing this number my whole life. It was a strange thing.”

Not surprisingly, Schmidt wasn’t really sure how to celebrate the feat. There were no balloons over the table waiting to be released if and when he broke the record. There were no television or newspaper reporters waiting to interview him. There was, in fact, a suddenness to the ending. The long journey was over.

“We just kind of cleaned everything up at the room and went back to the apartment,” Schmidt said.

After cleaning up at their shared apartment in Del Monte Forest along the scenic 17-Mile Drive, the Schmidts, along with Desmond and his wife Cecilia, celebrated at Monterey’s famed Whaling Station Steakhouse, perched above Cannery Row and overlooking Monterey Bay. The hero washed down crab and lobster with several glasses of his favorite cabernet sauvignon.

Having had time to digest the personal magnitude of his accomplishment and reflect on the long road he’d endured, Schmidt shared his thoughts.

“A lot of people think I did this for attention or so people can tell me I’m great,” he started. “I could have been on a deserted island and never met a soul, and I still would have kept trying to top 526. I’ve always been curious about whether I could do it. The skill that’s required to run, say, 250, is so immense that it boggled my mind that [Mosconi] could run 37 racks in a row without hooking himself or missing a ball. It became a personal obsession.

“There are some things that you KNOW you can do, and you’d bet your life on it. I didn’t know if I could do this.”

Not that John Schmidt is a struggling amateur. He has been a top American professional player for more than 20 years. He has won the prestigious U.S. Open 9-Ball Championship, numerous national and regional events, one-pocket titles and, of course, straight pool titles. He has played for Team USA in the Mosconi Cup twice.

But the Holy Grail for the 46-year-old from Hesperia, Calif., has never been a tournament title. It has been, at times, an unhealthy obsession with the number 526.

“This has been a journey of curiosity and self-discovery,” Schmidt acknowledged. “Sure, I love straight pool, but it was more than that. Could I challenge myself like this and hold my nerve together? Did I have the shot-making ability and pattern recognition?

Schmidt never needed an opponent to enjoy playing pool, and straight pool offered the perfect challenge of man vs. himself. The steep odds against him ever reaching 526 never deterred him.

“Just to have a shot after that many consecutive break shots is almost impossible,” Schmidt contended. “On top of that, over all those racks you don’t have a skid or a miscue or a treetop or a roll-off. Plus, you need the skill. Finally, you are shooting knowing that 65 years have gone by since that number happened. That adds pressure because Willie wasn’t shooting at a number. He just kept shooting. I had a specific number that I was chasing.

“Believe me, if anyone understood the odds, it was me.”

Through the years, Schmidt often set days aside to take serious runs at 526. His 400-ball run in Milton, Fla., in 2004 earned him the moniker “Mr. 400” and cemented his reputation as a straight pool big shot. He topped 400 again three years later in Virginia, reaching 403. Only a handful of players had reached that rarified air, including Billiard Congress of America Hall of Famers Earl Strickland (408), Allen Hopkins (421), Ray Martin (426) and Dallas West (429). While legend claimed that New York’s Michael Eufemia had run 625 in the 1970s, the closest recognized run to Mosconi was Germany’s Thomas Engert’s 491.

In 2013, a thread about challenging Mosconi’s 526 drew attention, with Schmidt offering to play 6-8 hours a day, five days a week in an effort to top the mark if someone or some company would give him a $50,000 salary. While discussion was lively, there were no takers.

In March 2018, Schmidt decided it was time to take a concerted run at the hallowed number. He packed up his motor home and drove to Monterey, where the owners of Easy Street agreed to give him a dedicated table over a 26-day period. Schmidt arrived at Easy Street 18 mornings during that period, cleaned the table, polished the balls are embarked on his runs. Incredibly, Schmidt posted 23 runs of 200 or more balls and peeled off 300-plus-ball runs on five consecutive days.

“I was amazed,” he remembered. “Then I realized I was still 200 balls away!”

It was during what became known as “John Schmidt 14.1 Challenge I” that Desmond suggested a different arrangement for the next attempt. Desmond, a 71-year-old retired sales manager, had been making the drive from his Saratoga, Calif., home to Monterey each morning (66 miles) to assist Schmidt with polishing, cleaning, racking and charting. Desmond offered to rent a two-bedroom apartment in Monterey in November and December for Challenge II. The team shopped for food, ate together, watched tape, discussed the day’s efforts and formulated strategy for the next day.

The addition of normalcy to Schmidt’s life made a distinct difference, with Schmidt posting two runs north of 400 balls, including a personal high 434.

“Again, I was still 100 balls short,” Schmidt said, exasperated.

In late January 2019, Schmidt traveled to Southern Indiana to play in the annual Derby City Classic. Naturally, he competed in the George Fels Memorial Straight Pool Challenge, in which players post an entry fee and get a dozen chances to post the event’s high run from a break ball position. (Schmidt posted the fourth-highest run, with 216.) During the event, Phoenix poolroom owner Trent King approached Schmidt with an offer to spend four weeks in Arizona and continue his quest at Bull Shooters, with each session streamed live to pool fans around the world.

The Arizona trip proved to be a turning point for Team Schmidt. While Schmidt authored another personal best – 464 – and ran through five more 300-ball runs, it was information away from the table that helped him turn a corner.

“I learned a ton of important things in Phoenix,” Schmidt said.

For starters, Schmidt started to change habits, change playing strategies and even change his attire.

“I bought a pair of Hoka shoes,” he said. “[Fellow pro] Mike Davis told me about them. They made a huge difference. My feet and legs didn’t get nearly as tired. I also started eating differently. I started fasting and drinking these B-12 smoothies from Whole Foods. I started breaking the balls differently. I was improving every day by learning what worked and what didn’t.”

Just three weeks later, the Schmidts and Desmond were back in Monterey for Challenge IV, a previously scheduled one-month stint.

“We’d already had the fourth block scheduled, so this was happening regardless,” said Schmidt. “And, truthfully, this was going to be the last block. Doug had spent a lot of money to help us, and it was costing me a lot of money too.”

On the second of the 16 days Schmidt played in May he ran 421.

“That gave me high hopes,” Schmidt recalled. “Then I had about a 10-day lull of high 200s and low 300s.”

Perhaps the most astonishing factor in Schmidt’s four-block assault on Mosconi’s run was his perseverance and mental fortitude in the face of 200- and 300-ball “lulls.”

While every long run and new personal high were great achievements, they were, at the same time, failures.

“If I was at Derby City and ran 400 I would be the hero,” Schmidt offered. “I’d be carried off on everyone’s shoulders and I’d have eight people trying to take me out to a nice dinner. But in this environment, there is no fanfare when I mess up. I feel like an idiot and I have to start over. It’s the only time in my career where I’ve done things that I would normally think are great and I feel like the biggest loser on the planet.

“I had hundreds of days that just were not fun. People think a lot of pros can do this, but I want to see how they react after they get a skid at 390 or a miscue at 275, day after day. When you’re on a big run everyone is watching. They’re all off their phones and their jaws are hanging open. Then when you screw up everyone just walks away.

“It’s an awful thing when you miss,” he added. “The livestream in Phoenix was good because it forced me to just rack the balls and start over. There were times I just wanted to break my cue and walk out of the building. But I kept going because I thought at any moment I could reach greatness. There were times I ran a 330 and followed with 170 on the very next shot. That’s hard to do when you’re disgusted.”

The mental focus it takes to endure hours of shooting, days on end, also took a physical toll on Schmidt.

“Some days I would walk in and run 100 four times in a row,” said Schmidt. “Now it’s noon and I’m already worn out. I still have a half day left. Or I’d run 360 and it’s after 6 o’clock. I’ve run past dinner, but I keep playing. Then I get a skid. My whole body is messed up.

“In Phoenix there were a number of days where I’d walk in and run 360 on the first or second shot,” he said, laughing at the recollection. “Now my feet hurt, my neck hurts and we’ve just started. It’s streaming live and people are yelling, “Yeah! Let’s put on a show!’ Meanwhile, I’m dying.”

Still, by Challenge IV, Schmidt’s new routine was paying dividends. In the evenings, Felicity would make dinner while John and Desmond logged the days numbers and discussed strategy.

“We constantly tested things,” Schmidt said. “Sleeping more, sleeping less. Eating more, eating less. Breaking hard, breaking soft. Every day, Doug and I were throwing stuff at the wall to see what would stick. Doug is a good player and is very knowledgeable. He’d say, “Why don’t we hit the break softer tomorrow?’ Or, “Let’s use high left on the break ball.'”

Schmidt would watch the evening news and retire early. Schmidt would rise by 6 a.m. and have his morning cup of coffee with Desmond. On the way to Easy Street, they would stop at Whole Foods to grab a few egg croissants and some fruit. Once at the poolroom, they would vacuum the table, polish the balls, close the drapes and start the camera. It became a ritual.

It was late in the day a week into his final trip to Monterey when Schmidt found himself deep into what he thought might be a record run. He cleared 450. Next, he blazed past his previous record of 464. Suddenly, he was knocking on the door of 500.

At 490, Schmidt faced a break shot to the right of the rack. It was a relatively routine break shot for Schmidt.

“I dogged my brains out,” Schmidt said in disgust. “And I will admit that it was 110 percent because of the pressure. It was right in front of me and I thought, “This is it.’ And I completely fainted. I let everyone down…Doug, my dad, my wife, my family, my fans. It was more heat than I could handle.”

Not surprisingly, Schmidt took a day of rest following the 490.

“Listen, I’m 46,” Schmidt confided. “I tried to wrap my head around accepting that failure was more likely than success.”

Twelve days later, on Monday, May 27, Schmidt strolled into Easy Street for another day of attempts. Unofficially, he had eight more days with which to break the record.

He wouldn’t need them.

Schmidt limbered up with 126, then 28.

“It was a perfect start,” he recalled. “I was still fresh. I had good energy. The conditions were perfect.”

So were his patterns. He blazed through rack after rack. When he got to his break ball, Desmond would calmly grab their trusty Sardo Rack and corral the balls for the next rack. A few hours later, Schmidt was well into the 300s. Soon after, he had topped 450 and the pressure began to build.

“470 to 530 I was a nervous wreck,” Schmidt admitted.

Ironically, at 490, Schmidt was faced with the very same break shot he’d botched two weeks earlier. Schmidt glanced over at Desmond, but Desmond refused to make eye contact. Schmidt felt nauseous.

“It was miserable,” he said. “If there was a heart monitor, I could have lit up an entire city.”

This time, however, Schmidt did not “faint.” The 5 ball sailed smoothly into the corner pocket and the cue ball dove into the rack, creating a nice spread of balls.

“Well,” said Desmond, matter-of-factly. “Engert is handled.” Having cleared two significant hurdles, Schmidt knew the record was in sight.

Schmidt broke at 504 and worked his way through the rack. At 518, Schmidt made the break ball, but the cue ball found its way into the middle of the rack. He feared the worst. Would he end up tree-topped or trapped? The balls seemed to move in slow motion. At the last second, the balls opened up and Schmidt saw a lane. He had one shot, a missable ball along the rail. It forced him to elevate his cue.

Suddenly, the panic, fear and nerves all set in. To Schmidt, virtually every shot the rest of the way looked nearly impossible.

“My heart was going a million beats a second,” he insisted.

Having successfully dodged that bullet, Schmidt knew Mosconi’s elusive 526 was in this single rack. A few balls later, Schmidt opened up a small cluster of balls.

“You need four,” Desmond offered.

The balls were right in front of him for the taking. Strange thoughts started to creep into Schmidt’s mind. What if they’d miscounted? What if they moved the coin (used to count racks) wrong and he was really only at 512?

So after Schmidt returned from his bathroom break to pocket 526, there was no celebration. No jumping up and down. No hugging.

“I didn’t want to beat the record by two balls,” Schmidt rationalized. “I wanted to put up a number that might last as long as Willie’s did. I know how hard it is to run this many balls.”

Schmidt continued for another 100 balls, finally missing on a combination at 626. “It was a shot that I could have made, but it was very missable,” Schmidt said. “If the run had to end, that’s the way I wanted it.”

Not surprisingly, news of Schmidt’s run blew up pool’s corner of social media. The New York Times heralded the accomplishment and a local Monterey television station did a short piece with Schmidt. Fans and fellow pros offered their congratulations.

“It is my proudest moment,” acknowledged Schmidt, “and the fanfare and congratulations from my fans and peers was way more than I thought it would be.”

The news, however, also sparked debate over the merits and significance of Schmidt’s 626. Critics claimed Mosconi’s run, completed in an exhibition match, was made during “competition,” while Schmidt simply set up break shots to start his runs.

“The criticism and skepticism have bothered me, to be honest,” Schmidt said of the posts. I can’t believe some of the things people have said. To me, it’s a small-minded mentality. In the end, though, it’s been about one percent of the comments.”

It appears that the Billiard Congress of America, recognized keeper of the sport’s official rules and records, has found no fault with Schmidt’s run. In early June, Desmond flew to the BCA office in Colorado with the unedited videotape. BCA officials Rob Johnson and Shane Tyree watched the entire four-hour plus video, and while no official statement has been released, the BCA is expected to recognize Schmidt’s effort as a “record exhibition high run.” It is also expected that the run will be submitted to the Guinness Book of Records.

In the meanwhile, Schmidt has been huddling with friends and advisors to discuss the best ways to capitalize on the record. An edited (for time) version of the video has been prepared but has yet to be released.

“Honestly, I have no idea what I’m supposed to do with the video,” Schmidt confessed. “I’ve got to monetize this to a degree. I don’t really make money in pool. It is an opportunity for me and I can’t let that pass by. I’m not going to simply release this video for free and end up dying broke behind a Walgreens. If the world won’t allow me to get something from this video, then I guess the world will never see it.”

Schmidt contends that he has not shot an inning of straight pool since Memorial Day. “I really want to put together a nice run the next time I step to the table,” he said. “It’s ego and pride. It’s important to me to run 250 or 300. The inning after that I won’t care.”

How Schmidt’s 626 will be remembered in pool lore remains to be seen. Will it carry the same mystique as Mosconi’s 526? Will it last as long?

Schmidt isn’t sure himself, but he is understandably proud of the effort and the result.

“I feel like this whole journey brought the pool world together a bit,” he said. “It was nice to see everyone talking pool and talking about straight pool again.”

MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN

Mark Wilson announces his resignation as Team USA Captain, today, Dec. 22, 2016.

I had a lot of time to think on the flight home from London, where Team Europe pasted Team USA in the Mosconi Cup. The final score was 11-3, which is bad enough. But it was the way Team Europe rolled to victory that really gave me pause. The Europeans were machinelike in their execution. They simply didn’t miss. They didn’t make mistakes. It was actually a beautiful thing to watch. For the stats-driven fan, Europe posted a collective .899 Total Performance Average over the four days. A .900 TPA is considered “world class.”

Professional level is .850. Team USA’s cumulative TPA during the event was .838. The difference is glaring. The beat down was so thorough, talk spread through the event that, after 23 years, the Mosconi Cup’s future could be in peril.Matchroom’s Barry Hearn even went so far as to announce his intention to start a Europe v. Asia event, to “test the Europeans.” Personally, I don’t buy the notion that the Mosconi Cup as we know it is in peril. At least, not yet. Defenders point out that the U.S. dominated the early years in the same way. During those years, however, Europe was continually closing the gap. Anyone who has watched the last five Mosconi Cups can see that the gap between the sides is widening.

What I see, though, are ticket sales and television deals that have grown exponentially over the past fouryears. Europe against the U.S. in tiddlywinks would draw a passionate crowd. Still, it is painfully obvious that Team USA needs to do something dramatic to make this a horserace again.

Which brings us to Mark Wilson. Three years ago, Wilson, one of the game’s top instructors and most ardent supporters, presented Matchroom with a three-year plan to get Team USA back on track. He stripped down the squad and rebuilt it based on character and commitment. In his spare time, he generated more interest and enthusiasm in the U.S. for the Team USA “program” than anyone before.

The results? The first year of the experiment resulted in a one-sided match, which was somewhat predictable. The second year showed promise, with Team USA gamely battling well into the final day. The third year, however, was a disappointing step backwards. As it is wont to do, social media exploded with posts slamming Wilson and the team. A handful of self-proclaimed experts shamelessly threw their hats into the ring as replacements for Wilson. Here’s a tip: Posting your intentions on Facebook pretty much eliminates you from serious consideration.

So, what’s the answer?

I don’t think anyone in the U.S. is more qualified than Mark Wilson, and I have far too much respect for him to suggest that he be replaced as captain of Team USA, but even he acknowledged that is a possibility. After all, the Mosconi Cup is Matchroom’s product, and they certainly don’t need to explain or apologize to anyone for taking the steps necessary to ensure continued growth and success.

So, in the event Matchroom does find it necessary to make a change at the helm of Team USA, here is my suggestion: Johan Ruijsink.

For those not familiar, the Dutch-born Ruijsink captained Team Europe seven times between 2006 and 2014 and posted a 6-0-1 record.

I know. I know. He’s not American. I realize Willie Mosconi just spun in his grave.

Just hear me out.

Johan Ruijsink is one of the world’s top instructors and coaches. The 50-year-old Dutchman took over Team Europe during those years of American domination and turned the squad into the fierce competitors that they are today. His first year at the helm was 2006, when his team tied the Americans, 12-12. After that, Team Europe won six times against zero defeatswith Ruijsink in charge.

Think he was simply fortunate enough to take over Team Europe as they were peaking? The last time Team USA won (2009), was one of only two times between 2006 and 2014 that Ruijsink was not Europe’s captain.

Now, about that “he’s not an American” argument.

Who says the coach must be American. Sports history is littered with instances of foreigners running national teams. Were Americans offended when Romanian gymnastics coaching legend BelaKarolyi took over Team USA and turned it into a gold medal machine? Were American soccer fans up in arms when Sweden’s PiaSundhage took over USA Soccer’s women’s program and produced a pair of Olympic gold medals? The bottom line is to maximize Team USA’s chances of not just competing in the Mosocni Cup. The bottom line is to drive Team USA to win the Mosconi Cup. Of course, Ruijsink is much more than simply a once-a-year-captain. He is a coaching legend in Europe. A former top Dutch player, Ruijsink turned to coaching in the ’90s. His small, six-table room in The Hague was open only to players committed to training. Ruijsink’s training methods turned Holland into a European power, with the likes of Rico Diks, Alex Lely, Nick Van den Berg and NielsFeijen turning their games over to him.

A voracious student of training and coaching techniques, Ruijsink earned a Master Coach degree from the Dutch Olympic Committee in 2000. It is the highest coaching education in Holland, allowing him to coach any sport. Over the past two years, Ruijsink has been coaching in Russia, where the Russian federation hired him to develop its crop of talented young shooters, like Konstantin Stepanov, RuslanChinakhov and rising star Maxim Dudanets. Ruijsink will be bringing his Russian brigade to the Derby City Classic in January.

Trust me on this one. If change is necessary, this is the right man for the job.

Of course, there are questions I can’t answer. Would Matchroom go for such an idea? Hearn is a pretty shrewd operator, so I’d have to guess this idea has already crossed his mind. And given the fact that he desperately wants to see the U.S. competitive again, and the fact that he loves a good storyline, I can’t see why he wouldn’t entertain contacting Ruijsink. Would Ruijsink consider coaching Team USA? Can’t say for sure, but two years ago he told me he was stepping down as coach of Team Europe because he “didn’t see the challenge in coaching Team Europe any longer.”

The $60,000 question, though, is this: Would American players put aside their egos to be coached by a foreigner? Unless they are more pigheaded and self-absorbed than I imagine, they should.

I guarantee one thing: Announcing Ruijsink as Team USA captain would scare the living bejeezus out of Team Europe.

Gene Nagy Dies at Age 59

Gene Nagy, legendary straight-pool player and longtime coach and mentor to many players including Jeanette Lee, passed away yesterday, July 13, at age 59.

Visitation will be held this Sunday, July 16, from 2-4 and 7-9 p.m. at:

Kearns Funeral Home

61-40 Woodhaven Blvd.

Rego Park, N.Y.

(718) 441-3300

Nagy died of emphysema and cancer of the lungs. He is survived by his aunt, Jean O’Brien, and many close friends and students.

Nagy was born Oct. 6, 1946 in New York. Before he became a highly respected pool player he was an accomplished musician. He started playing the trumpet at age 12 and attended the Juilliard School of Music at age 17.

Nagy didn’t start playing pool until he was 18 years old, and by the time he was 23, he was invited to his first professional tournament. His lifetime personal high run of 430 is topped officially only by Thomas Engert, Min-Wai Chin, and Willie Mosconi. He is also known for running 150 and out in the 1973 World Straight Pool Open against Allen Hopkins.

Luther Lassiter was quoted as saying of Nagy, “That man was born to play this game.”

Willie Mosconi commented on Nagy’s style, saying, “It was the finest I had ever seen balls taken from the table.”

By the late 1970s, Nagy had retired from competition, but continued to teach and mentor young players. Jeanette Lee, famous the world over as “The Black Widow” was one of his best students, and considered him a father.

Lee said of Nagy:

“Everything I know, I learned from him. He was my coach, my mentor, my friend, my father, my everything. Particularly for the first five years or so, when I first started playing pool.”

Lee met Nagy when she was 19, through her then boyfriend, at a New York poolhall.

“From really that day on, he played me everyday of my life until I moved away. The poolroom opened at 11 a.m., we got there at 10, had coffee, and played until they closed at 11 at night. He never kept score. He really taught me the love of the game to always stay a student.”

Lee credits all of her ability to Gene, as well as her character. She says that he taught humility by example. When she hit her first high run of 122, the very next inning, he ran 238.

“He’s the one who really gave me compassion and gave me humility. People probably wouldn’t call me that, but as a student of the game I am. What it came down to was, he just taught me to love pool for the love of the game, above and beyond any kind of competitiveness or materialism or glory you could take from it. That’s where my willingness to want to give back to this sport and do things for the growth of the game itself, comes from.”

Lee also dedicated her 2001 book, “The Black Widow’s Guide to Killer Pool” to Nagy.